|

| I have visited this spot many a time. |

I have often said that this piece is as beautiful for its concept as for the execution of that concept. In four movements Ives portrays the spirit of four writers who lived during the Transcendentalist movement in New England in the mid-nineteenth century. This was a movement that emphasized the basic goodness and decency of people, and organized religion and government were seen as a threat to that purity. Ralph Waldo Emerson, the subject of the first movement of the sonata, crystallized the general feeling of Transcendentalism in an 1836 speech: "We will walk on our own feet; we will work with our own hands; we will speak our own minds... A nation of men will for the first time exist, because each believes himself inspired by the Divine Soul which also inspires all men."

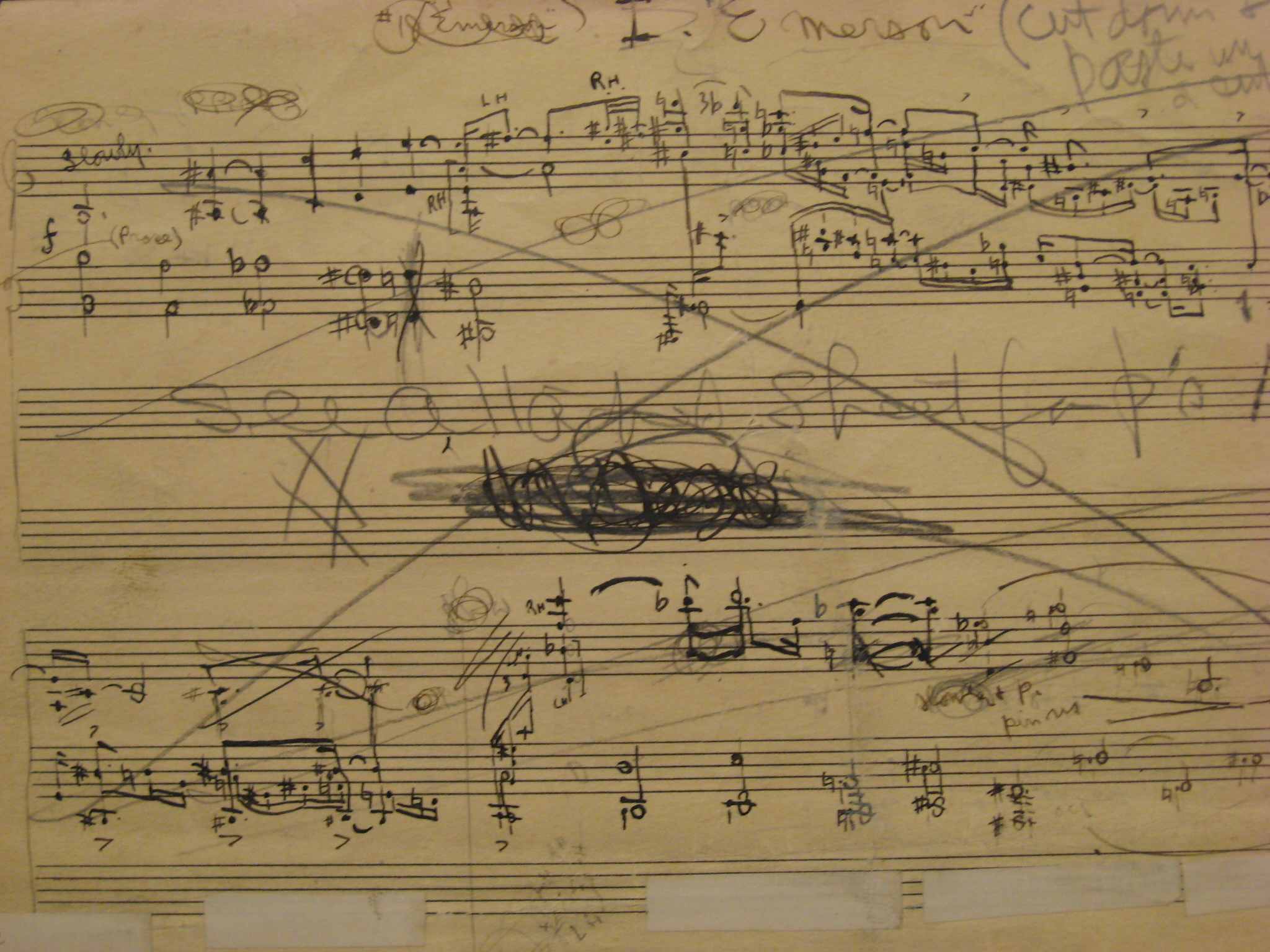

Of the four writers, Emerson was the most important to Ives. This is evident in the fact that the Emerson section of the sonata also existed as a piano concerto and an overture, and that Ives continuously tinkered with this movement, claiming that it was never quite finished.

Nathaniel Hawthorne is an odd choice of subject for the second movement, since he was actually opposed to Transcendentalism. He believed all men were inherently evil, and most of his stories focus on Puritan guilt. Thus, he serves as sort of a foil.

The third movement is titled "The Alcotts", referring to Louisa May Alcott and her family. In the context of the sonata, this represents the idea of simple living; Louisa's parents were involved in a Transcendentalist community living experiment called Fruitlands, and Louisa's literature illuminates the joy of the common life.

Finally, Ives closes with a movement based on Henry David Thoreau, who also valued simple living but took it to the extreme, retreating into nature for a prolonged period. By ending with Thoreau, Ives makes the intriguing statement that perhaps the answers to some of life's deepest questions lie in nature.

Now on to the music. The Concord Sonata is very cyclical, with short themes that appear in every movement, in varying transformations. It traces a path from extreme dissonance and density to absolute clarity at the end of the Alcotts movement, before returning to austerity for Thoreau. It is difficult to describe the music itself in great detail, but I did write some program notes when I performed the Emerson movement on my junior recital at Wheaton. Here's an excerpt:

"From a performance standpoint, the Concord Sonata presents a unique set of challenges. Any serious performer approaching the score is likely to be baffled by Ives's footnote: '…there are many passages to be not too evenly played and in which the tempo is not precise or static; it varies usually with the mood of day…a metronome cannot measure Emerson’s mind and oversoul, any more than the Concord steeple bell could'. The writing is dense, often notated in three or four staves, and a certain Yankee ingenuity is required to account for every note in Ives's massive chords. In keeping with the Transcendentalist spirit, the sonata is intended to be a virtuosic tour de force, an American answer to Beethoven’s Hammerklavier. Indeed, the piece rivals Beethoven's great sonata in its motivic saturation (with fragments of Beethovenian themes, no less!), and in its exploitation of both percussive and textural piano effects. The second movement contains passages of tone clusters to be played with a strip of wood, and the final movement briefly requires a solo flute.

The fact that the Concord Sonata still sounds radical to our ears today is a testament to Ives's imagination and artistic courage. Right from the outset, it explodes with barbaric chords and polyrhythms. The opening four notes of Beethoven's Fifth Symphony appear repeatedly, with many different harmonic and psychological implications. Ives conjurs up a tour de force of sound: grinding dissonances that seem to scream from the keys, distant church bells, splashing arpeggios. There are moments in which all the little themes piles up on top of each other, like several people trying to talk at once, only to dissolve into some kind of grand Transcendentalist statement. Ives lovingly captures the chaos and awkwardness of American life, a wackiness that cannot be notated in 4/4 time or arranged in neat diatonic harmony. The fact that the Concord Sonata still sounds radical to our ears today is a testament to Ives's imagination and artistic courage. The piece still bears the label of 'difficult music', but I do agree with Lawrence Gilman's assessment of its greatness*. I hope you enjoy the ride."

I will quickly address the companion readings to this piece before this post becomes too unwieldy. First, Ives's own Essays Before A Sonata are a great demonstration of his brilliance, not just in music, but as a thinker. In the Prologue, he hits the reader with one weighty question after another, mostly about the idea of portraying concepts and/or concrete objects in music. He poses these questions about evaluating the success of programmatic music even as he is writing an extremely highbrow programmatic piece.

|

| The piano at the Alcotts' Orchard House. |

The short essay about The Alcotts brings a very important point to light; he mentions the spinet piano in the Alcotts household "on which Beth played the old Scotch airs, and played at the Fifth Symphony". Here he makes the connection between the simplicity of the New England household and the revolutionary spirit of Beethoven, because in the nineteenth century, a typical American's first experience with the classical canon would be not in the concert hall, but in the home. In this way the seemingly plain lifestyle of these people touches on something bigger, more immense, even divine. And at the end of the Alcotts movement of the sonata, as the Beethoven theme rings out in rich, triumphant C major, this quotation from the essay summarizes the effect: "All around you, under the Concord sky, there still floats the influence of that human faith melody, transcendent and sentimental enough for the enthusiast or the cynic respectively, reflecting an innate hope— a common interest in common things and common men—a tune the Concord bards are ever playing, while they pound away at the immensities with a Beethovenlike sublimity, and with, may we say, a vehemence and perseverance—for that part of greatness is not so difficult to emulate."

One last point to make about that particular movement is that, in the process of laying out his artistic philosophy in this piece, Ives also makes a case for tonality as an arrival point. After two movements of the most hardcore dissonance, the climax in C major feels incredibly majestic, because it is earned.

Kyle Gann's essay concerns Henry Brant's orchestration of this piece, which I had the privilege of hearing live in Chicago. In some ways the orchestration is a great gift; being able to hear orchestral colors and notice melodic lines that were previously hidden in the texture has helped me greatly in my piano interpretation. But the piece also loses something as a symphony. The piano is a solo instrument, and as such the most intense moments are really visceral, bursting with virtuosic derring-do. When I perform the climaxes of Emerson, Hawthorne, or The Alcotts, I have to give my entire physicality to the music and pour my heart into it as well. The experience of hearing a performer's struggle to victory in this music is more electric than hearing a whole orchestra. It's that kind of piece, and I think that's the way Ives intended it.

It is now quite late. Hopefully I will be able to adapt some of these thoughts to my presentation tomorrow, and also play some excerpts convincingly.

*In another part of the program notes I included a quotation from Lawrence Gilman's review of the public premiere of the piece, where he recognized it as the greatest music ever composed by an American.