Me at the summit of Pine Mountain, where Ives used to sit and contemplate nature.

But Ives means more to me than that. His music is a near-perfect representation of America, vacillating between aggressive, boundary-shattering dissonances and retreats to nostalgia. These two styles are often in conflict, even in the same piece. Ives loved patriotic tunes and the hymns of church traditions, and he gleefully inserted fragments of these songs into his music wherever possible.

For now I'll refrain from talking about the Concord Sonata, which is absolutely my favorite piece of music and which I consider one of the greatest pieces ever written. The introductory listening for Ives was Three Places In New England and The Things Our Fathers Loved.

It seems a bit strange that Three Places In New England has become the go-to Ives piece to program in an orchestral concert. It is not completely audience-friendly. The first movement, also the longest, does not have much interest beyond some lush string chords and tasteful dissonances in the piano (always a part of Ives's orchestra). But when we get to Putnam's Camp, it is vintage Ives (though, knowing both the Concord Sonata and the Fourth Symphony, I experience major déja vu at the opening). The polyrhythms are fascinating, and the evocation of an out-of-control marching band is quiet novel. All the patriotic tunes would come across as pandering to the audience if they weren't wrapped up in such a sophisticated framework.

The final movement, The Housatonic at Stockbridge, most completely captures the New England spirit of this piece. Ives takes one of his best art songs and adapts it to an orchestral canvas, and the effect is extremely exciting. Muted strings run up and down in the background like a slight breeze, hinting at possibilities. The vocal line is played by the cellos, and dissonant notes on the glockenspiel trickle into the ear. I've read that this piece was composed shortly after Ives's marriage. He and his wife shared an intimate walk along the Housatonic River, talking about the future that lay ahead of them. I love the fact that Ives captured this moment and then orchestrated it, magnifying it. It reminds me of the dialogue surrounding the pivotal wedding in Thornton Wilder's Our Town, as the townfolk speculate on another young couple getting married. By getting married, they get a glimpse of the profound, transcendental truths underlying the quiet life in their town. I think that what Wilder did in that play is exactly what Ives did in his music: examining the simple, common decency of people and taking it to a place of exaltation.

Since I think it's worthwhile to compare the original voice-and-piano version of The Housatonic at Stockbridge with the orchestral version, here are both versions back-to-back. I wish I could find an online version of Jan DeGaetani singing this, but alas, this will have to do:

And the orchestra:

The other Ives piece on the list was the song "The Things Our Fathers Loved". In this piece I hear more of that deep American nostalgia, and also Ives's penchant for employing the whole-tone scale and sometimes touching on a Scriabinesque mysticism.

Carl Ruggles was a contemporary of Ives, but I don't know nearly as much about him, aside from the fact that Ives supported him. At a concert of Ruggles' piece Men and Mountains, Ives noticed many hecklers in the audience and said something to the effect of "Don't be afraid of strong music like this - use your ears like a man!"

Unfortunately, Ruggles does not hold a candle to Ives. Sun-Treader is modernistic and pioneering for its time, but there is a distinct lack of personality. Even though Ives can sometimes be opaque and frustrating to listen to (even by a self-proclaimed fanatic), there are unique trademarks of his style: quotations, distant bells, manic ragtime breakdowns. There is a sense of philosophical reasoning behind the music. Ives always wants to get a message across.

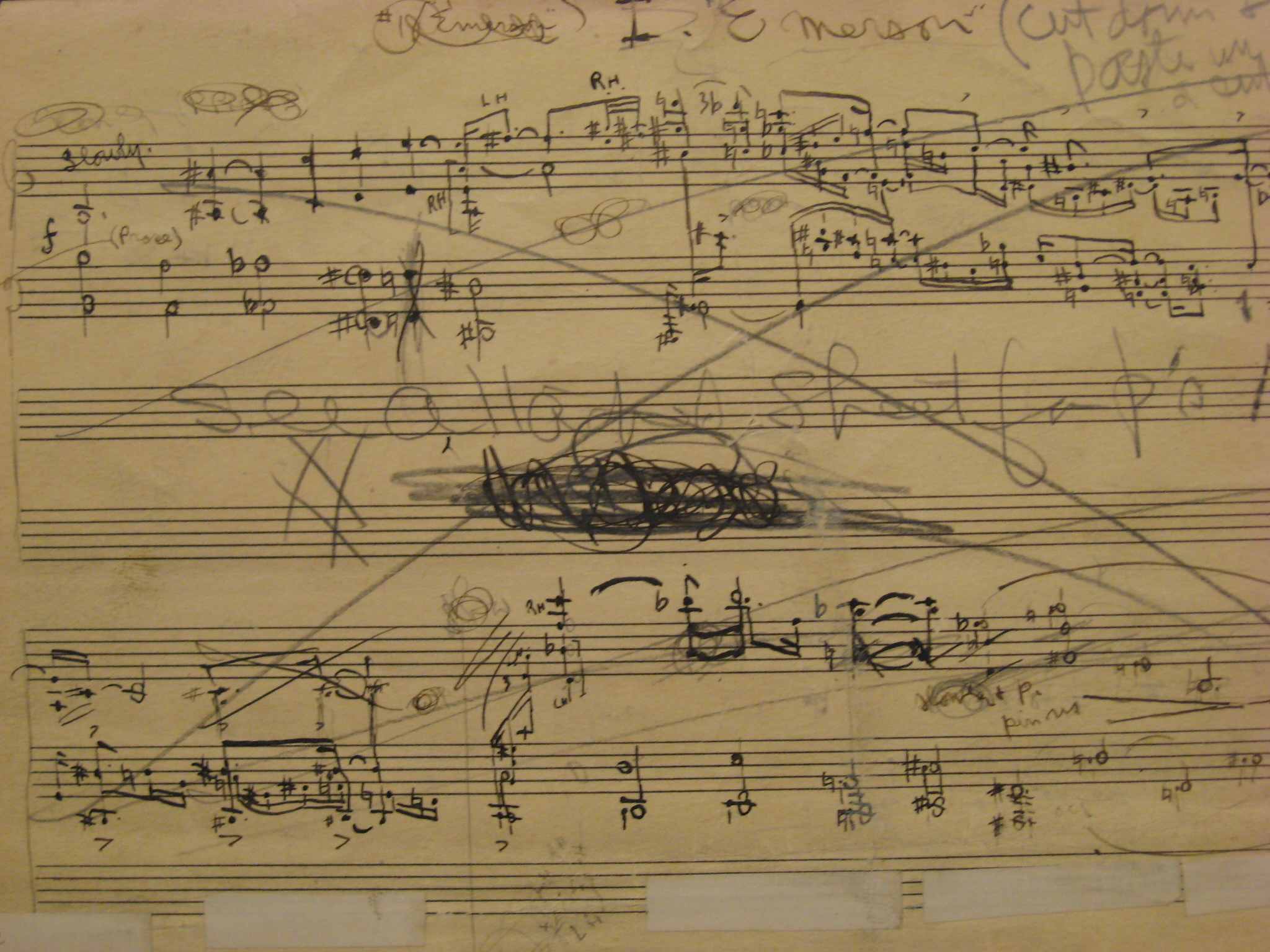

If there's one advantage Ruggles has over Ives, it is that his music sounds "cleaner" and that it is being played from a well-edited score. Ives left much of his scores in complete shambles, with incoherent marks and differing editions that gave publishers headaches. But this can be attributed to the fact that he was essentially an amateur composer, writing in the evenings after he returned from selling insurance, and also from the fact that he disliked the whole classical music scene.

The messy manuscript of Ives's Concord Sonata.

This post has only scratched the surface of Ives and what he means to the American canon. Next time I will attempt to write about the Concord Sonata.

No comments:

Post a Comment