That exchange intrigued me greatly, so I went ahead and found a recording of that particular scene. It was the first time I had really engaged with Einstein on the Beach, and I could instantly see why Gann was so enamored of this music. It is sublime from beginning to end.

Between this excerpt and the other parts I heard in a documentary, here's the first thing that stands out: Einstein on the Beach makes the best case for the synthesizer of any piece I've heard. It's a keyboard instrument, so it doesn't require much stamina to sustain arpeggios for minutes at a time, and because it has an electronic tone, somehow it remains detached from a perception as accompaniment. It just IS. The attack is always the same, with no decay, so it maintains the hypnotic quality Glass wanted in this music.

The documentary I watched was called Einstein on the Beach - The Changing Image of Opera. This was my first experience with the visual elements of the opera, and...wow. More sublimity. There was nothing alienating about it for me. I found the whole spectacle to be beautiful, ecstatically slow, and momentous. This is a piece about trying to get inside the head of a genius, experiencing thought and time from a different perspective, and meditating on genius itself and a celebration of genius and how it positively affects people. There is a futurist element to the opera, similar to the John Cage "happenings" that celebrated the arrival of the computer, but the total package is way more coherent and carefully crafted.

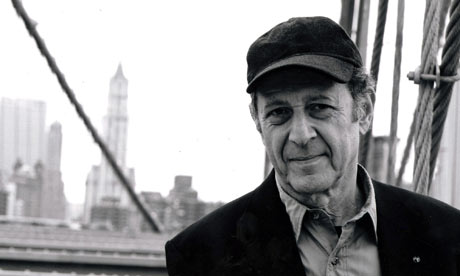

I facepalmed slightly at some of the interview scenes with Robert Wilson, the director and designer of the Einstein production at the Brooklyn Academy of Music. This man is such an Artist with a capital A, finding tortured, off-center positions in which to hold himself, smoking constantly, and talking in an over-meticulous way that suggests that he really likes the sound of his own voice. I imagine that as a collaborator he was exhausting to work with but also brilliant when necessary.

|

| Look at those eyes. Seriously. Look at those eyes. |

The interviews with Philip Glass, by contrast, illuminate his disarming sincerity and the light in his eyes. Anyone who thinks that minimalism, at least as produced by Philip Glass, is just a gimmick or a sham, needs only to watch this man speak to be proven wrong.

It's actually quite a joy to watch those interview segments interspersed with clips of the opera itself, because you can just feel the creativity and inspiration bursting forth.

I had a thought about why Glass-ian minimalism is so well-suited for the subject of Einstein. This music makes you THINK. An Elliott Carter string quartet makes me think, sure, but my brain is so busy trying to keep track of what's happening that I don't focus on what's happening moment to moment. In Einstein on the Beach, everything is repetitive: the pulses, arpeggios, vocal lines, dance movements. At some point it's all going to sink for the listener and maybe the listener will have some epiphany about the human race, math, science, joy, somewhat akin to what Einstein had in his life. It's also been proven that repetitive music like techno or dance pop (or Glass) can focus brainwaves, creating a conducive environment for deep thought.

Allright. That's probably enough geeking out over Einstein on the Beach for now.

Next I listened to an excerpt from Akhnaten - Amenhotep's funeral scene. The contrast was startling. Instead of abstract performance art onstage, there was clearly a story being told. It was also the most uptempo funeral music I've ever heard. I liked the effect of the fast music and the hearty unison singing from the ensemble, but it started to wear on me slightly. Still pretty cool.

I read an article by Timothy Johnson (an Ithaca professor whom I really want to talk to!) about the various definitions of minimalism and their inherent problems. He argues that the best categorization of minimalism is as a technique, as opposed to an aesthetic or style. He points to the explicit harmonic motion and large-scale design of a piece like Music For 18 Musicians; while it is repetitive and comprised of simple materials, it does have harmonic goals and musical development in mind. This is all to rebut the points put forth by people who try to put Reich and Glass under the same umbrella as La Monte Young, whose pieces arguably do not have these same formal considerations.

Johnson quotes John Adams and his take on minimalism as a personal influence: "Minimalism really can be a bore - you get those Great Prairies of nonevent - but that highly polished, perfectly resonant sound is wonderful." I love that! Great Prairies of nonevent. He seems to acknowledge that there's something very American about the movement: the openness, quiet positivity, the excitement of new beginnings, the catharsis and healing of simple consonances after a tumultuous time in history.

In a way, writing with minimalist techniques (I have to be careful here) must be uniquely satisfying for a composer. The listener is able to perceive almost every element of the piece's craft, and there's something miraculous about a piece that holds one's attention through the most subtle changes in rhythm or register or texture.

HERE BEGINS SECTION TWO: PERFORMANCE ART

I watched a breezy little video about the history of performance art, narrated by Frank Skinner, and in which I saw familiar figures like John Cage, George Macunias, and Yoko Ono. The video took an unexpectedly dark turn, though, delving into some of the most extreme performance art of all time, like a man submerging himself in some kind of black liquid in a bathtub for days, surrounded by excrement. Or a guy who zipped himself up in a tarpaulin and laid out on the highway. Or Marina Abramovic, who famously laid objects of varying potential for violence out on a table and invited the audience to use them on her. I think it's important that we live in a society where this kind of art is not the only kind of art, but I appreciate it for what it is. It makes us think about who we are, what's we're doing, and it creates a kind of vital, primitive humanness between the performer and the audience.

Next on the listening list were two pieces by Meredith Monk. The first one, Earth Seen From Above, confused me. It was a mesmerizing video of the International Space Station's view of Earth, sped up to a great degree. The underpinning music was a bit ambient and chill, based on a two-chord progression, and fit the visuals well. I guess I was expecting something that related more to performance art. But the visuals were stunning nonetheless. I saw flashes of thunderstorms flying past, the lights of cities, and most importantly, majestic views of the Northern Lights.

The other Monk piece was called Dolmen Music. Again, there was no video to accompany the music I heard, so I could only imagine what would be transpiring onstage. All that was provided was a still image of Meredith Monk in a semi-reclined position on the stage. The music was definitely beautiful, haunting, and poignantly constructed. Some extended vocal techniques played an important role, with many fast nonlingual syllables. The other musical materials I perceived were repetitive phrases, echo and imitation. Very beautiful stuff. I just wish I knew more about the context or meaning. I guess I'll have to seek that out.

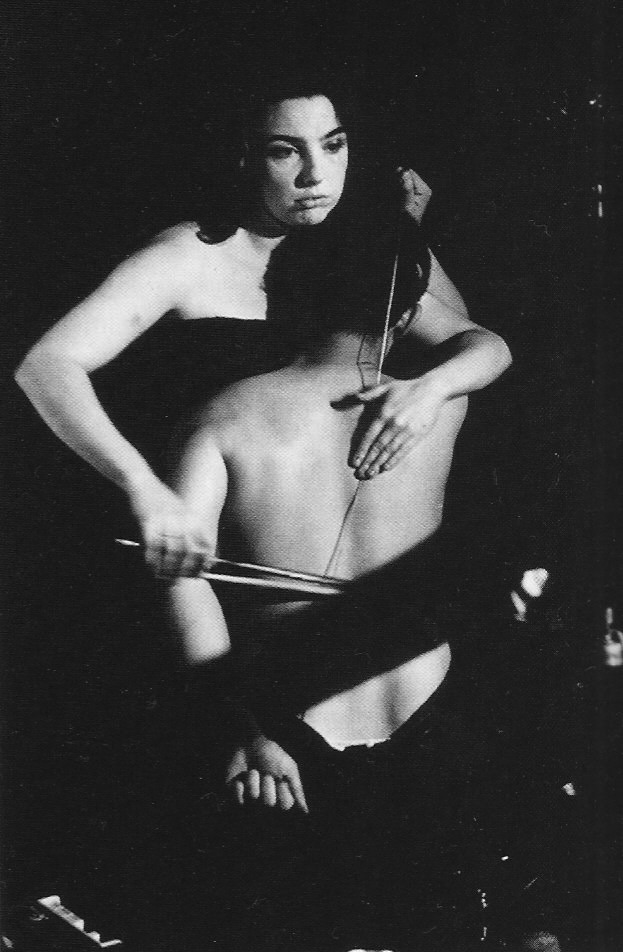

|

| Before Lady Gaga, there was this woman. |

Then I watched a performance of Laurie Anderson's O Superman. This piece has an appealing facade, aligning itself with a pop idiom. It almost feels like an extended intro to some kickass 80's tune. I was basically waiting for the drums to come. But they never did. Anderson was wearing dark leather, her hair was wildly spiky, and she had exaggerated eyeliner. Together, these elements had a subversive effect. The song seemed pretty political, a commentary on American culture: "When love is gone, there is always justice/ and when justice is gone, there is always force/ and when force is gone, there is always mom". There were also repeated references to "the hand that takes". And the Ha syllable, repeated through the entire piece, seems more and more feeble by the end. I read about this piece on Wikipedia, and found that some of the thematic material is actually inspired by Massenet's opera Le Cid, so there's actually a lot going on here.

Ha ha ha ha ha ha ha ha ha ha ha ha ha ha ha...