Catherine Moorman, a cellist, describes how she grew bored of her life as a mainstream classical performer, daydreaming in the middle of her own solos. And therein lies the paradox. Musicians become bored of the predictability of the classical canon, so they migrate to the world of new music. But there they have to deal with potentially extreme intellectual and physical demands, forceful composer personalities, and a smaller audience, that, while attracted to this music, may still not understand or enjoy the work of a particular composer. New music does not have the protective seal of retrospect. It has not been exposed to audiences for enough time for a definitive critical opinion to form, or for an enthusiastic following to develop. Performers are usually taking a risk in learning this music, because it may not be worth the trouble. Only time will tell.

|

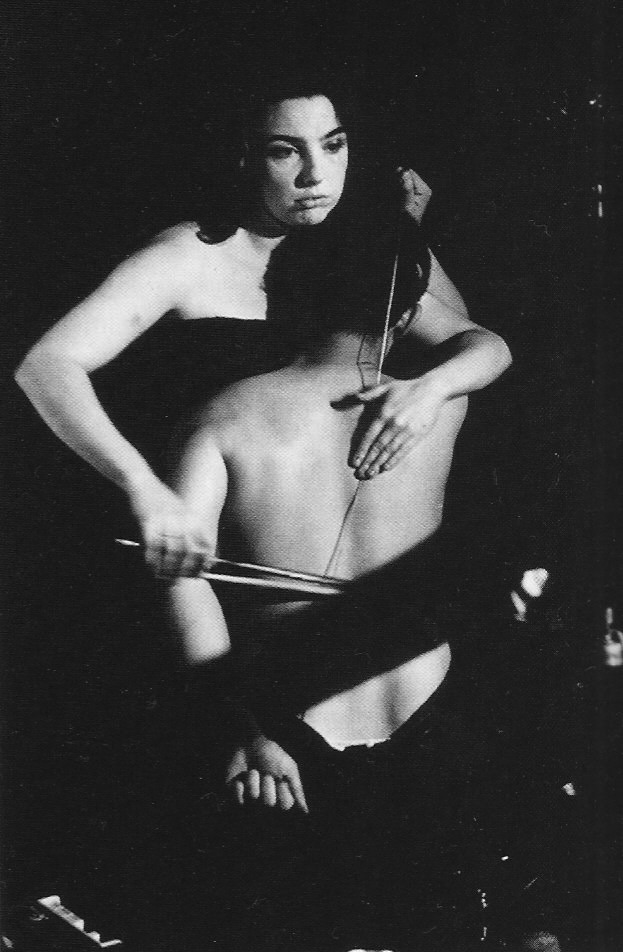

| Catherine Moorman plays Nam June Paik as a human cello. |

The other conflict is between the composer's desired outcomes for a piece and the actual outcomes in performance. John Cage apparently had some major issues with Catherine Moorman's performances of his piece 26' 1.1499". Though she worked diligently, she incorporated some erotic and explicit physical actions (along with the hijinks of Nam June Paik) that pushed Cage's boundaries. Here we see the tension between Cage wanting to let performers have free rein over his work, but also not wanting them to get carried away with infinite possibilities.

I briefly perused the Fluxus Performance Workbook. Fluxus, of course, is the larger movement surrounding John Cage and the downtown Manhattan scene in the 60's, built on anti-art, anti-government ideals and some Dad influence. This workbook contains hundreds of conceptual chance pieces that are simply lists of instructions to produce a performance, or in some cases, an action that is not even performed on stage, like mailing a treasured item to someone....or peeing on subway tracks. Pretty far out. I don't know what to think of the more impractical concepts. Would there be any value in actually carrying out those instructions? For example, dragging a bunch of broken dolls along a street would not be interpreted by the average person as a piece of performance art. But it might make them think about things. And maybe that's the point?

I watched a video of Pauline Oliveros' piece "Teach Yourself to Fly". The premise is that any number of people sit in a circle in a dimly lit room and start to breathe, slowly introducing pitch and then increasing in intensity. The results were quite beautiful and unearthly. I'm sure that the feeling of being in that room would be akin to a religious experience, electric and confusing and scary and thrilling. And I think that's what Oliveros was aiming for: something to take people outside of the everyday realm and into a slightly higher plane.

Next I listened to James Tenney's Chromatic Canon. A New York Times profile on Tenney notes that he has worked in a large variety of media and styles, from highbrow electronic music to film scores and ragtime. He's a true maverick. This particular piece combines a minimalist aethestic with a slowly building 12-tone row. The piece maintains a very calm, consonant sound for the first minute and the first four or so pitches of the row, but then dissonances intrude and the soundscape becomes really unsettling, even mind-altering. I wanted it to stop but at the same time I was hypnotized. I'm glad I listened to the end because eventually the tone row was stripped back down to the opening consonant pitches, returning to an equilibrium.

I had the unique privilege (?) of hearing Alvin Lucier's I am sitting in a room live at the Bang On A Can Marathon in 2012. Coincidentally, Pauline Oliveros and her Deep Listening Band were also present. This piece really tests my patience, but I appreciate the concept. Lucier reads the following text:

I am sitting in a room different from the one you are in now. I am recording the sound of my speaking voice and I am going to play it back into the room again and again until the resonant frequencies of the room reinforce themselves so that any semblance of my speech, with perhaps the exception of rhythm, is destroyed. What you will hear, then, are the natural resonant frequencies of the room articulated by speech. I regard this activity not so much as a demonstration of a physical fact, but more as a way to smooth out any irregularities my speech might have.

|

| There he is. |

It's kind of awesome that the concept of the piece is clearly stated in the text that is the piece itself, so the audience knows exactly what's going on. Because wow, it happens so gradually. By the last few minutes (after about forty minutes), Lucier's voice has transformed into plangent ambient sounds with musical pitches. The experience of hearing this live was pretty memorable, partly because the room in question was the Winter Garden at the World Financial Center, a huge, resonant rotunda. The other neat aspect was the changing light through the enormous window overlooking the Hudson River. It was late afternoon, and the hazy sunlight filtering into the room enhanced the feeling of melting into the room.

|

| The Winter Garden at the World Financial Center, New York, where the Bang On a Can Marathon is held. |

No comments:

Post a Comment