|

| I wish I knew how to quit you. |

Enough about me though (for now). I read an article from the ever-enlightening NewMusicBox about the history of the musical "look back", of composers consciously borrowing elements from the past. The author suggests that this falls into three categories: imitation, emulation, and quotation. Numerous examples from history support each category, but I'll focus specifically on the assigned listening for today. They are all obviously from the twentieth century, which makes them all the more fascinating; the twentieth century was the most risky time to attempt either a quotation or full-on imitation of older, tonal styles. The author offers Kyle Gann's take on this phenomenon: "Quotation allowed a return to tonality hidden beneath a veneer of irony; it offered a widened emotional palette without sullying the composer’s fingers in the actual writing of tonal or pretty music." That man has such a way with words.

Each of the pieces on this listening list employs quotation or imitation for a different reason. I'm finding it hard to organize my ideas here, so I'll resort to a list format:

George Rochberg - String Quartet No. 3

Quotation/Imitation: Imitation

Composer quoted/imitated: Beethoven, Bartok

Why: Rochberg started out as a serialist (and listening to one of his Bagatelles for Piano is proof), but after the death of his son he found that an atonal musical language was not sufficient for conveying his feelings.

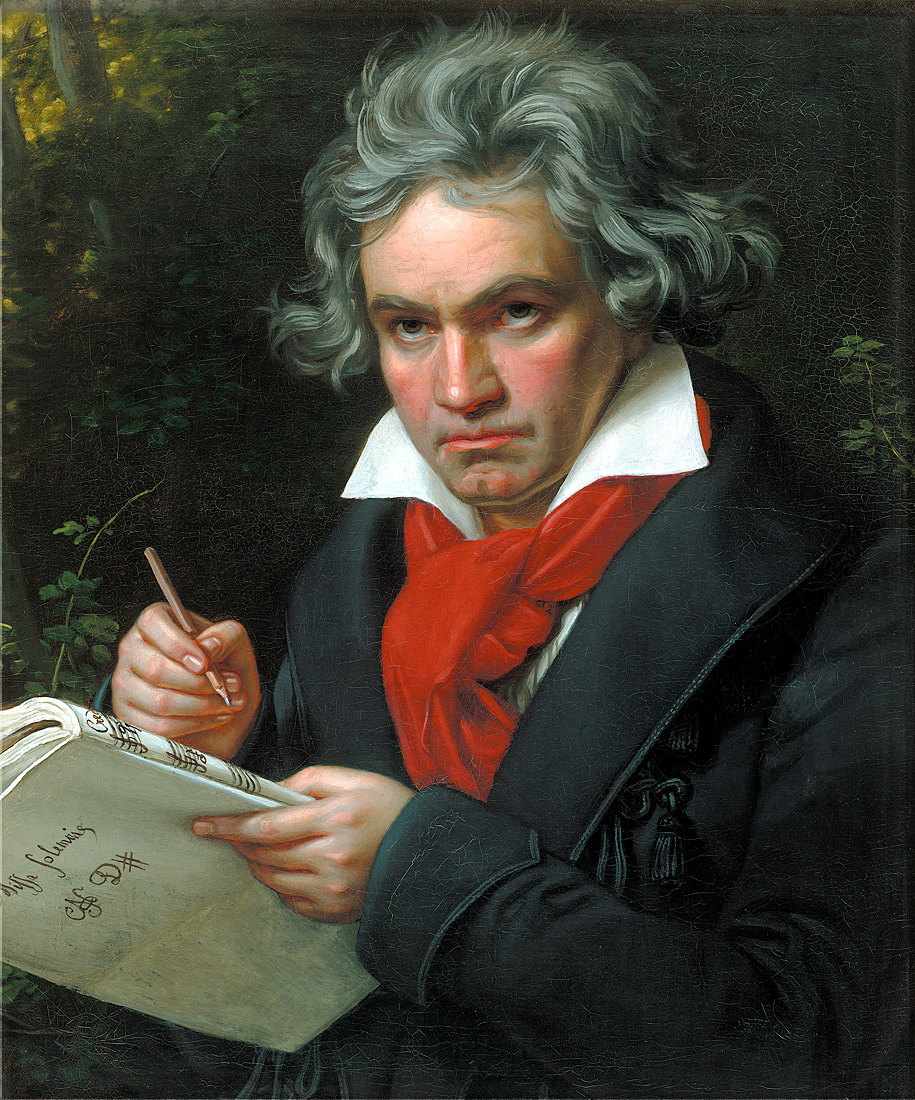

Description: The Third String Quartet begins with a sharp, dissonant gesture, but the first movement passes through several sections of warm consonance that recall Beethoven's own string quartets, and some folky, energetic sections that bear striking similarity to Bartok. One of the primary motives in this movement is a tentative descending whole-step gesture that conveys Rochberg's indecisiveness about which style to settle on. Then in the second movement, we are treated to a full-on, fifteen-minute Beethovenian adagio. Rochberg produces a very convincing imitation of Beethoven's style, with lots of I-6 chords and angelic high violin lines, and in the same variation form Beethoven liked to use in these movements. Is this artistic resignation or cowardice? Or is it a daring, honest personal expression? The third movement begins with more Bartok, but revisits Beethoven again before ending on a Bartokian note. This piece, taken as a whole, is both a personal emotional statement and a view of the composer grappling with the string quartet tradition itself.

George Crumb - Black Angels

Quotation/Imitation: Quotation

Composer quoted/imitated: Schubert

Why: Crumb inserted the variation theme from Schubert's Death and the Maiden string quartet to add a sense of timelessness to an apocalyptic piece.

Description: Black Angels is a piece about destruction, death, and religious strife, written in a primarily dissonant and abstract aesthetic. The Schubert quote has a striking effect when it arrives unannounced after five minutes of some of the darkest, most disturbing music I know of. In the score, this section bears the text "Like a solemn consort of viols". This is interesting because it makes the quotation slightly anachronistic. If Crumb really wanted to emulate fifteenth-century viols, one would think he would use music from that period. But the Schubert quote just goes to show that certain musical constructions have a timelessness to them; the mournful, desolate quality of Death and the Maiden knows no historical limits. As the Schubert is played by three of the instruments, a lone violin hovers high above, like a last bird or insect surveying the ruins of civilization. This is honestly one of my favorite moments in all music. The effect is incredibly profound.

I should also mention that the movement headings in this piece ("Departure", "Absence", and "Return") are taken from Beethoven's Piano Sonata No. 26 "Les Adieux". Scholars have written in detail about the significance of using those titles to point back to Beethoven, but I think it's a bit of a stretch.

John Adams - Grand Pianola Music

Quotation/Imitation: Imitation

Composer quoted/imitated: Beethoven

Why: John Adams was trying to reflect his experiences walking through San Francisco Conservatory and hearing multiple piano students playing washes of arpeggios in pieces like Beethoven's Emperor Concerto. He also based this piece on a dream in which he was driving along Route 1 and saw two long black limousines transform into pianos playing arpeggios of E flat major and B flat major. Conveniently, E flat is Beethoven's heroic key and the key of the Emperor Concerto.

Description: This piece starts out in typical Adams fashion, with repetitive figures and static, suspended harmony. Eventually three wordless sopranos enter as a trio; they represent a group of three sirens (as seen in Greek mythology). It is not till the third movement that Adams goes full Beethoven on us (with dashes of Liszt and Liberace). This movement is titled On the Dominant Divide, and is full of bombastic progressions from I-V-I in different combinations. It ends resolutely E flat major.

Now, this piece has an interesting history. It was booed at the premiere, which, to be fair, was a concert of mostly academic, serial pieces from Princeton and Columbia. The audience probably interpreted it as some kind of lame, tacky joke. Adams did not intend this piece as a joke per se, but a parody for sure and a good-natured "Whitmanesque yawp". He was just being a little goofy, and could always fall back on the defense that he was just writing about his weird dream. I read somewhere that he deliberately tried to construct the most awful, clumsy semi-Beethovenian theme possible out of the I-V-I progressions. But the public doesn't always get highbrow musical humor, and this piece has been embraced by a lot of people who view it as a sincere Romantic statement. Isn't that wonderfully ironic? The most educated listeners may have gotten the joke, but they hated the rebelliously tonal trappings of the piece, and meanwhile the average concertgoer just gravitated toward the accessible harmonies while blissfully ignorant of Adams' intent.

Adams' own program notes from his website provide more insight into this piece, if you can put up with his usual self-aware, self-congratulatory tone.

Frederic Rzewski - The People United Will Never Be Defeated!

Quotation/Imitation: Imitation

Composer quoted/imitated: Imitation of classical variation form, especially the model of Beethoven's Diabelli Variations

Why: Somewhat open to interpretation, as I'll discuss below.

Description: I could write a long essay about this piece, but I'll try to be concise. Basically, Rzewski makes a clear Romantic statement with this piece. He writes an overwhelming set of 36 variations (on a Chilean protest song popular in the 70's) that surpasses the Diabelli Variations in complexity and duration, and, as if to acknowledge the Transcendental spirit of this endeavor, he includes an optional six-minute cadenza for the pianist to improvise. So much about this piece brings me back to Ives: the use of a popular patriotic tune for melodic content, a political element, shattering virtuosity, and extended piano techniques.

But there is more going on here than a simple appropriation of a Classical formal design. I see some kind of symbolism in the use of thirty-six short variations to portray a social struggle. In the same way that a large group of people would be heartily singing this tune, perhaps each variation is a portrait of a different individual involved in the conflict. Rzewski ends each set of six variations with a weird kind of retrospective, revisiting the textures and moods of each past variation in hasty, fragmentary fashion. What is he trying to say? That each of these people was killed or otherwise silenced by this oppressive regime? In addition to these possibilities, the improvised cadenza seems like an opportunity for the pianist to offer commentary on this political situation, or to choose which variations to revisit and meditate on. It's all very interesting.

No comments:

Post a Comment